Schaulust

11 June – 18 July 2015

June 11, 2015 6-9 pm

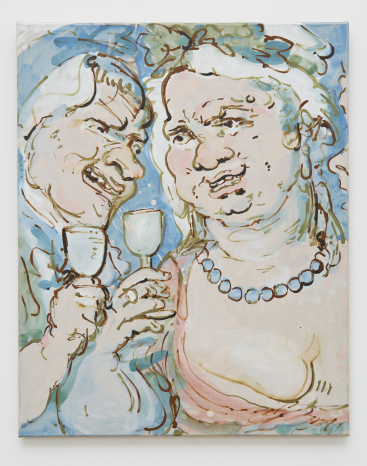

Charlie Billingham

Touche Éclat, 2015

Oil on Linen, 75 x 60 cm

Touche Éclat, 2015

Oil on Linen, 75 x 60 cm

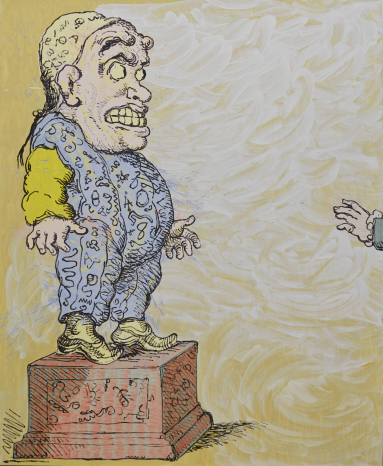

Charlie Billingham

Deep and Learned, 2015

Oil on Polyester, 220 x 180 cm

Deep and Learned, 2015

Oil on Polyester, 220 x 180 cm

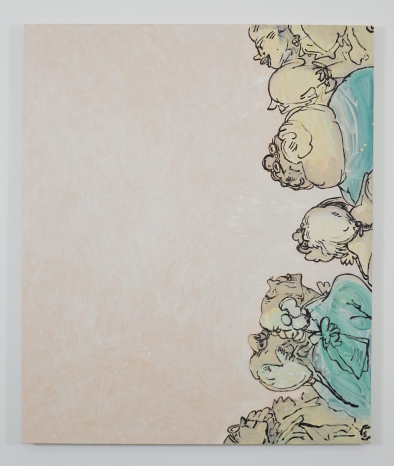

Charlie Billingham

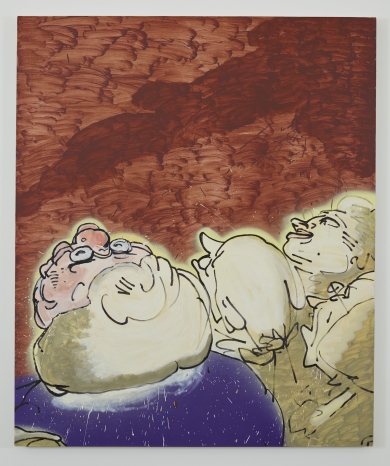

Scopophilia, 2015

Oil on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Scopophilia, 2015

Oil on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

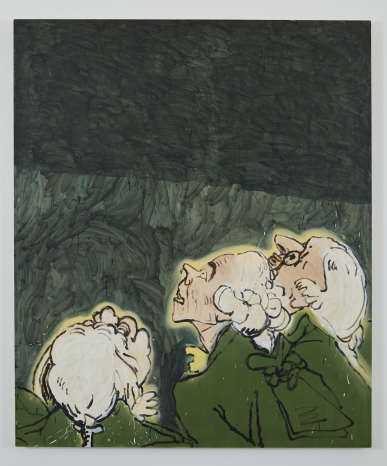

Charlie Billingham

The Show Must Go On, 2015

Oil on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

The Show Must Go On, 2015

Oil on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Charlie Billingham

In Bloom (detail), 2015

Oil on Linen, marble, brass, steel, 18th century Delftware ceramic, fresh cut flowers, water

147 x 80 x 60 cm

In Bloom (detail), 2015

Oil on Linen, marble, brass, steel, 18th century Delftware ceramic, fresh cut flowers, water

147 x 80 x 60 cm

Charlie Billingham

In Bloom, 2015

Oil on Linen, marble, brass, steel, 18th century Delftware ceramic, fresh cut flowers, water

147 x 80 x 60 cm

In Bloom, 2015

Oil on Linen, marble, brass, steel, 18th century Delftware ceramic, fresh cut flowers, water

147 x 80 x 60 cm

Charlie Billingham

Enlightenment, 2015

Oil and Acrylic on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Enlightenment, 2015

Oil and Acrylic on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Charlie Billingham

Curtains Up, 2015

Oil and Acrylic on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Curtains Up, 2015

Oil and Acrylic on Linen, 180 x 150 cm

Charlie Billingham

Post Horn, 2015

Oil on Linen, brass hinges, 200 x 280 cm

Post Horn, 2015

Oil on Linen, brass hinges, 200 x 280 cm

Charlie Billingham

Mouthpiece (detail), 2015

Oil on Linen, woven tapestry, gesmonite, acrylic paint

488 x 300 cm

Mouthpiece (detail), 2015

Oil on Linen, woven tapestry, gesmonite, acrylic paint

488 x 300 cm

Charlie Billingham

Mouthpiece, 2015

Oil on Linen, woven tapestry, gesmonite, acrylic paint

488 x 300 cm

Mouthpiece, 2015

Oil on Linen, woven tapestry, gesmonite, acrylic paint

488 x 300 cm

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Charlie Billingham "Schaulust"

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015

Installation view at Supportico Lopez, Berlin 2015